The Legendary Stunts That Built Old Hollywood

Dec 2, 2025

Zach Wilson

These Old Hollywood stunts are foundational to how stunts are performed and respected today. In this article we explore iconic stunts, stuntmen, and how the craft has changed over time.

Buster Keaton standing under the fallen house in Steamboat Bill, Jr.

Buster Keaton: the falling house and the train work

Buster Keaton planned stunts down to an inch.

In Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) Keaton stood in front of a real two-ton house façade while it dropped around him. The crew marked the exact spot he had to hit. If he had moved an inch, the stunt would likely have killed him.

This moment is one of the most documented and verified single-shot stunts from silent-era cinema.

Keaton also performed dangerous train stunts in The General (1926). He ran across moving cars, jumped from engine to tender, and rode on the cowcatcher in sequences that used real locomotives and real speeds. Those stunts required precise timing and risked severe injury or worse.

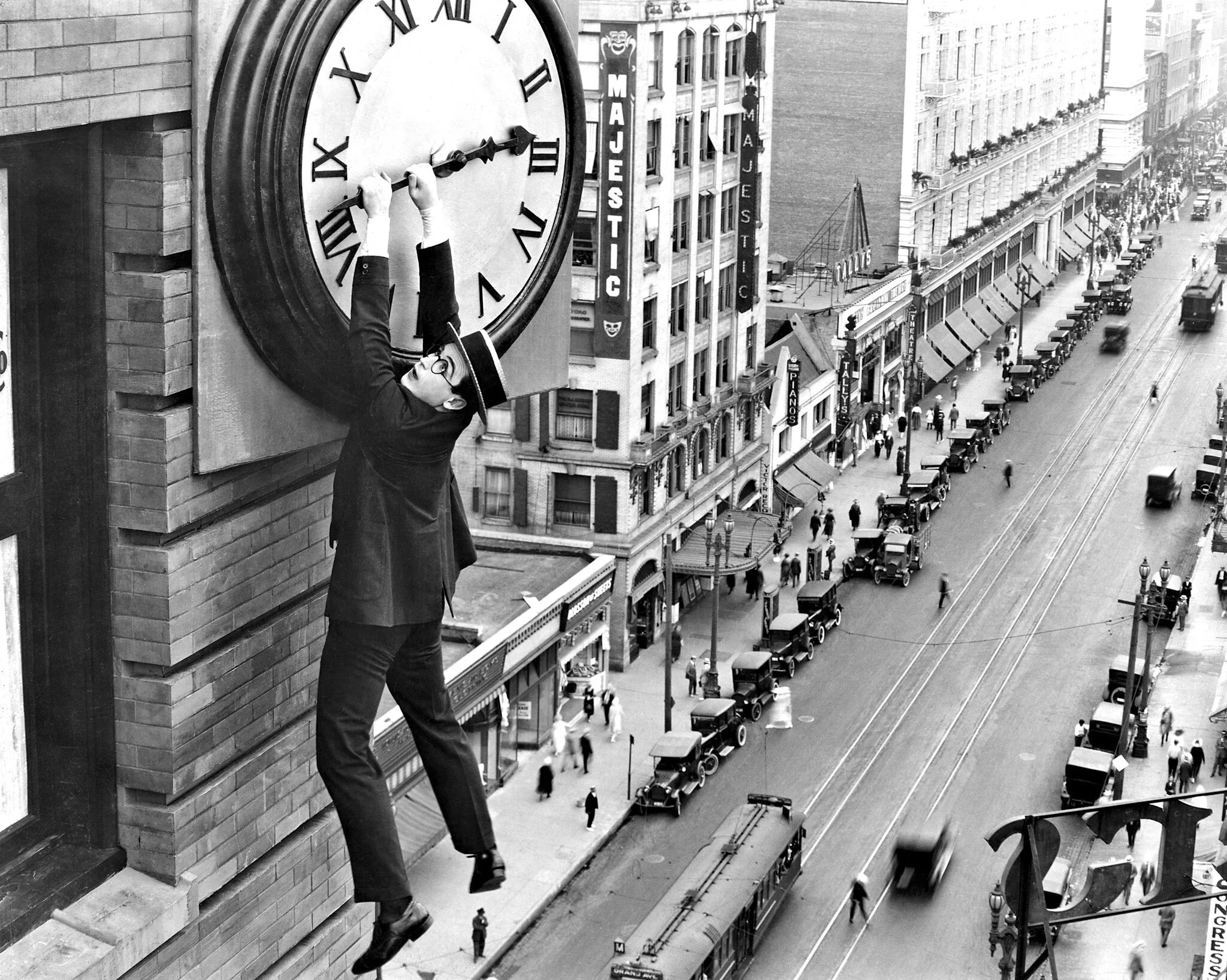

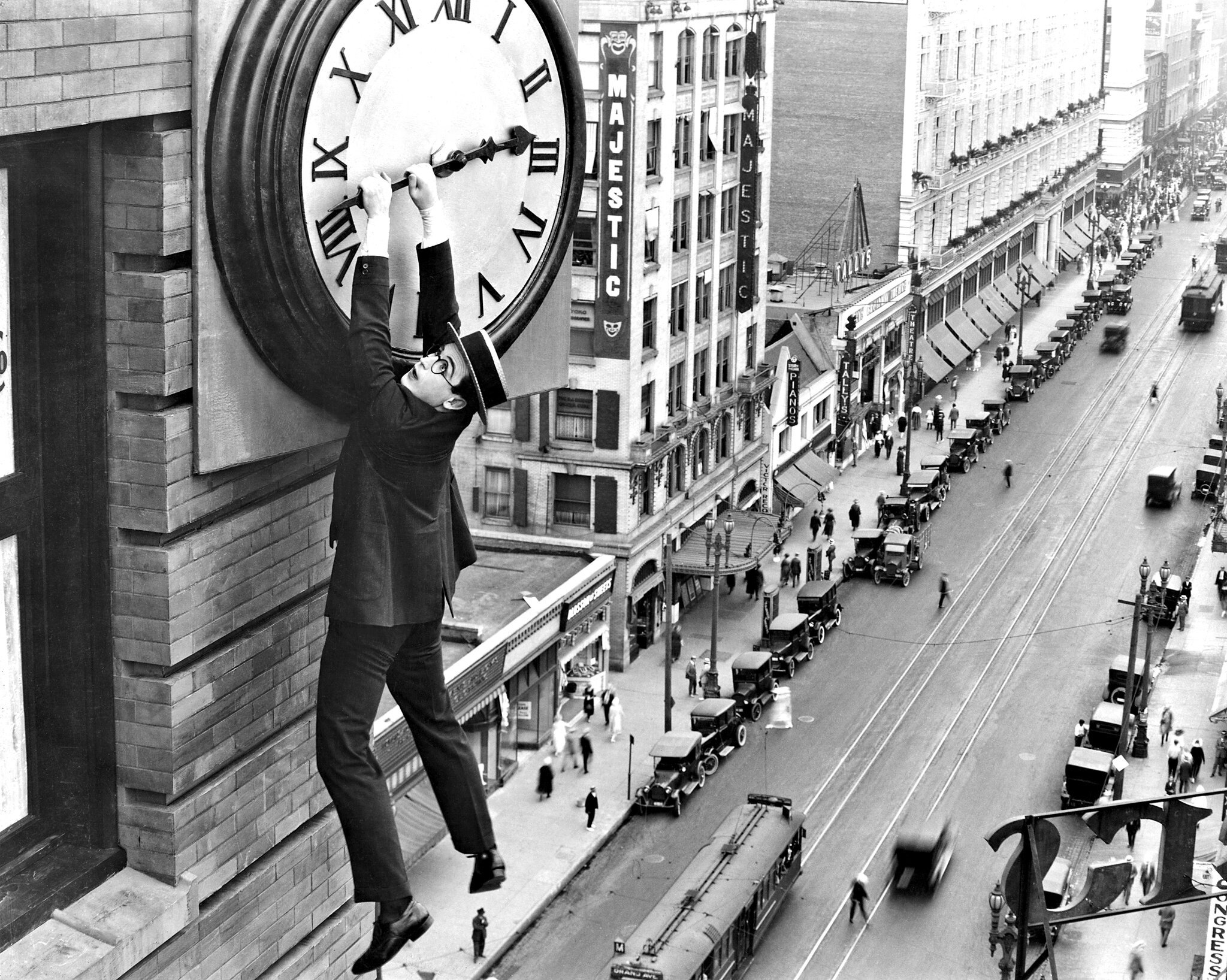

Harold Lloyd’s iconic “Clock Stunt” in Safety Last

Harold Lloyd: the clock shot and how it was done

Harold Lloyd’s image of hanging from a clock face in Safety Last! (1923) is iconic.

The shot used an elevated platform and careful camera placement to make the drop look higher than it was. Lloyd did perform the stunt on a roof and used limited set protections, which still left real danger in the take.

The platform and camera angles gave the illusion of great height while reducing risk, but the stunt remained hazardous and required exact execution.

Yakima Canutt, the “Stuntman Pioneer”

Yakima Canutt: the stunt pioneer who changed the craft

Yakima Canutt moved stunt work from cowboy skills to repeatable, film-safe techniques.

He performed the famous stagecoach-to-horse transfers in Stagecoach (1939) and developed rigging, harnesses, and the L-stirrup that improved rider safety.

Canutt also designed controlled wagon and horse-fall methods and helped systemize stunt coordination. His methods became the foundation for modern stunt rigs and second-unit action direction.

The rise of professional stunt performers and groups

By the 1930s and 1940s, studios relied more on specialized stunt performers instead of asking lead actors to do every risky shot. Groups of stuntmen—often called “the Cousins” and other collectives—established standards, shared techniques, and pushed for better pay and safer practices. Over time these performers helped create training norms and organized labor protections through guilds and unions.

Early car chases, water drops, and fire scenes

Early action sequences used real vehicles, real water, and real flames. Car chases involved drivers sliding and crashing with minimal protection.

Water stunts required precise estimation of landing zones and breath control; performers often faced cold currents and debris.

Fire scenes used practical flames and limited protective gear.

These sequences gave films visceral realism but raised high risks for performers and animals. Sources on stunt evolution document the frequency and danger of these practical stunts in early Hollywood.

Judy Garland with her stunt double Bobbie Koshay in “The Wizard of Oz”

Stunt doubles and uncredited work

Many early stunt performers worked uncredited, doubling for lead actors in risky shots.

Notable names later became known: Richard Farnsworth began as a stunt rider before his acting career, and David Sharpe became a leading acrobatic stuntman.

The early stunt community trained on the job and developed skills that studios later formalized into second-unit roles and stunt coordination.

Safety evolution and industry recognition

Techniques and gear improved over time. Innovations from performers like Canutt introduced harnesses, breakaway rigs, and safer methods for repeated takes.

The Screen Actors Guild and later industry groups pushed for better insurance and standards. More recently, the Academy and industry bodies have been pressured to give stunt professionals formal awards recognition; the Academy announced a new stunt category to debut in 2028 for films released in 2027.

That decision follows long advocacy from stunt coordinators and performers.

Why these early stunts still matter

Modern productions use wires, airbags, digital cleanup, and CGI, but directors still value real stunts for tactile weight and danger that read on camera.

The craft techniques from Keaton, Lloyd, Canutt, and others informed stunt coordination, second-unit direction, and safety protocols. Their work changed how action is staged and taught a core lesson: planned risk, not reckless chance, makes a great stunt.